Texas TEKS Student Expectation for Fifth Grade

5.16.A.iii: Write imaginative stories that include dialogue that develop the story

The Challenge

It's difficult for my ELL's (English Language Learners) to fully grasp punctuation rules. We drop the inverted question marks and exclamation marks when they change languages, and so much of their cognitive power translating and functioning in a second language. (Something I feel equivalently anytime I step into a room of native Spanish speakers and I'm the only non-native speaker there.)

So, the challenge is that I want my fifth graders to be able to write imaginative, inventive stories, and dialogue, I know as a reader and a write, is massively important to creating engaging narrative, regardless of the level or age of the author.

The Process

Lesson 1:

Part I. I downloaded the declarative knowledge of what the word dialogue means and what it look like through abbreviate notes. (Also played a Brainpop video to one group for reinforcement)

Lesson 2

Part I: Brief verbal review of notes with emphasis on noticing punctuation marks.

Part II: Students copied examples of dialogue out on sentence strips. Then, I asked them to make a cut between the dialogue and the dialogue tag. After this, I asked them to cut off the comma, then the quotation marks, and finally the punctuation. I modeled with my own sentence how I could rearrange all the pieces to move the dialogue tag to the front almost like a magic trick. The students then tried to replicate the effect with their own manipulatives and I helped them. (Sometimes we had to make an extra comma or extra period, depending on the sentence.) Finally, students put their pieces into baggies and mixed the pieces up and challenged friends to reconstruct their sentences correct. For extra challenge, some cut the entire sentence into separate words as well. They loved the challenge.

Lesson 3

Part I: Whiteboards: Reviewed parts of dialogue and dialogue tags by showing sentences with no punctuation whatsoever and have students identify using the context only which part was dialogue and which part was tag. Whiteboards let me give immediate feedback.

Part II: Adding punctuation on whiteboards--students then started adding in correct punctuation on their own, but easily fixed with rapid teacher feedback.

Part III: Students used map colors to add in commas, question marks, exclamation marks, periods and quotation marks onto worksheets with prewritten dialogues.

Lesson 4: Scaffolded Dialogue Construction

We read part of an amazing wordless graphic novel by Shaun Tan called The Arrival.

Part I. The book is about an immigrant man passing through a surreal version of New York and adapting to life there.

Using whiteboards, we invented our own dialogue for the page, discussing and making inferences about what we think the characters might be talking about.

Again, using whiteboards at this point in the process helps me correct errors in the students' understanding of how to compose dialogue very, very quickly. This is very much "You do--I help" part of the guided release model.

Part II. Once students start so show proficiency, we moved to writing on notebook paper and practicing making correct indentations when we change characters. We also practiced the importance of paying attention to neatness and organization (skipping first line, pausing at the pink line and returning to the red line on standard notebook paper). We discussed as a class when we should or should not start new paragraphs.

Part II. Once students start so show proficiency, we moved to writing on notebook paper and practicing making correct indentations when we change characters. We also practiced the importance of paying attention to neatness and organization (skipping first line, pausing at the pink line and returning to the red line on standard notebook paper). We discussed as a class when we should or should not start new paragraphs.If you don't own this book, it's totally worth having in your library. It does an amazing job of making you feel like an immigrant in a foreign country while using dream-like imagery to provoke deep questions and thoughts--all without a single word in the entire book.This was still guided work, but with less support.

The next step is for students to compose the next set of dialogue on their own! More to come!

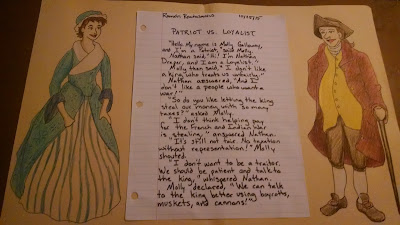

End Product Goal: Social Studies Integrated Project: Loyalist vs. Patriot Dialogues! [Coming soon!]